On Sunday 23rd of February we hosted Rojava Everywhere, a day in solidarity with the revolution in Rojava. The program consisted of many lectures and discussions on the ideas that inspired the revolution, on how they are put in practice there and on what we can learn and put into practice here.

We had comrades from the Internationalist Commune of Rojava visiting. The Internationalist Commune of Rojava is a self-organized collective of internationalists in Rojava, trying to support the revolution and also spread the ideas of the revolution outside of Kurdistan. They facilitate the participation of internationalists in Rojava and have also launched many campaigns over the years, the current ones are Make Rojava Green Again, Riseup4Rojava and Women Defend Rojava. We were also joined by a person from Ecologie Sociale Liege and by some people active in DemNed (the Kurdish Federation in the Netherlands) and the Kurdish Liberation Movement.

The day started already in the morning with a Seminar on Rojava and Ecology given by some comrades of the Internationalist Commune of Rojava. The seminar was meant specifically for people actively involved in the climate justice movement here in the Netherlands.

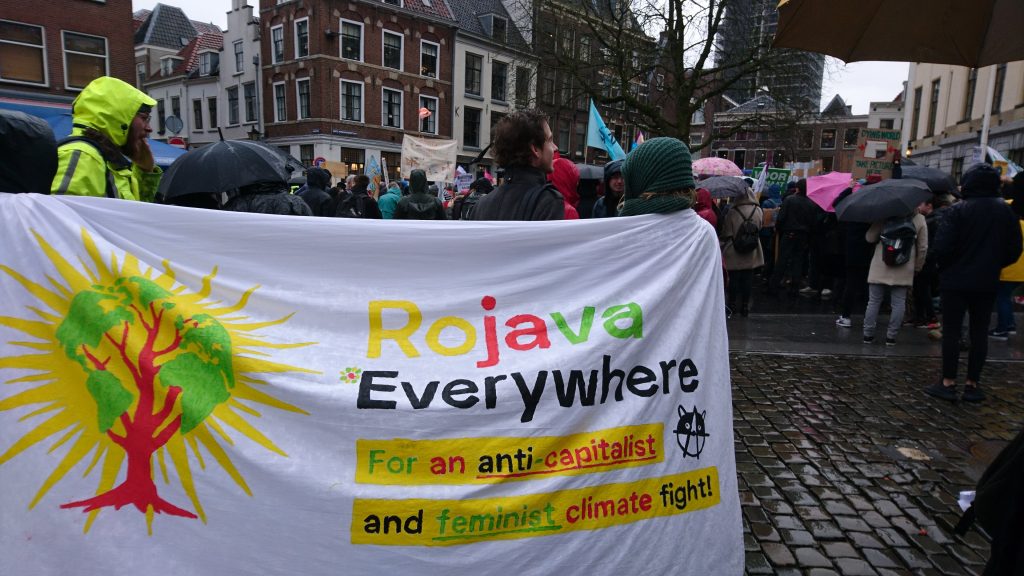

After lunch we continued with a lecture on the birth of Democratic Confederalism as a theory and its application in the region of Bakur given by some Kurdish comrades, followed by a talk about the ideas of Social Ecology and the Social Ecologist movement in Belgium. Finally, comrades from the Internationalist Commune of Rojava gave a talk about the role of Internationalists in the Revolution in Rojava and what can be learnt from there, and about the campaign Make Rojava Green Again. Also during the whole afternoon, people collectively participated in the making of a banner in solidarity with Rojava for the Climate March in Utrecht of February 29th.

The day was well attended and it gave people from different contexts and collectives the opportunity to exchange ideas and contacts. Many things were said and it’s impossible to give a complete recount of it, but we’ll try to mention some things in the following, these are of course just brief notes, we’ll add some links for people interested, for a more in-depth introduction we recommend the Make Rojava Green Again book that we have at our stand.

The Ecological Crisis as a Crisis of Capitalist Modernity

Something that was made clear in different talks during the day is the impossibility of understanding ecological problems as separate from the social structures in which they are originated.

This idea was already developed by Murray Bookchin in the 80s, where in his book The Ecology of Freedom he starts developing Social Ecology as a theory. Even if heavily inspired by Social Anarchism, Social Ecology is fundamentally marked by the reflection on the relationship between society and nature. Humans and society, according to Bookchin, were not to be considered “alien” to nature, but a continuum of it, making therefore ecological problems strictly dependent on social problems.

This same notion is also present in the Kurdish movement. The so-called Crisis of Capitalist Modernity is therefore understood as a combination of multiple, interlinked crises:

- the Ecological Crisis, with the ongoing destruction of the environment, the alienation of people from nature, etc.

There is no way of addressing one of them without considering the others and without considering the way in which society is organised. In his reflections, Abdullah Öcalan thinks back at the

The work of Make Rojava Green Again outside of Rojava is exactly that of spreading these concepts and notions in the ecological movement.

Democratic Confederalism as a concrete example for a Radical Change

Democratic Confederalism was introduced as the ideological paradigm of the Kurdish liberation movement as a way to radically change the structures regulating our society and make way for a radically democratic society based on women’s liberation and ecology.

Democratic Confederalism originated as a theory from reflections that Öcalan and other members of the PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party) had between the end of the ’90s and the beginning of the 2000s. Until then the PKK had been organized as a national liberation movement, with a Marxist-Leninist ideology, whose goal was the creation of an independent Kurdish State. However, after reflecting on the oppressive nature of the nation-state it became clear that it was not the Turkish State alone the problem, the problem was the nation-state itself. Creating a nation-state for the Kurds would therefore not end the other systems of domination (patriarchy, class system…) that were foundational to the nation-state as an organisation.

Therefore, influenced by thinkers such as Bookchin and Foucalt, Öcalan began envisioning a libertarian system of social organisation independent from the nation-state. Hence, Democratic Confederalism seeks to organize society from the bottom up and on a grassroots level based on self-management and mutual aid, with the goal that decisions should be taken at the lowest possible level (neighbourhood communes, city communes, etc.).

Democratic Confederalism, beside being an interesting libertarian theory, it is a theory that is being put in practice at the very moment. It is the theory behind the revolution in Rojava and the one through which, consequently, the Autonomous Administration of North-East Syria is currently organised. We also heard about the struggle for democratic confederalism in Bakur, and some concrete examples of how it was put into practice there, before the repressions by the Turkish State.

Learning from the Revolution: Rojava Everywhere

Organizing this event for us was a very nice experience and, beside giving the opportunity of speaking with a lot of comrades, and hearing and reflecting on very interesting topics, made us even more conscious on the importance of establishing stronger connections with the Kurdish movement here in the Netherlands.

In a context where we are deprived of the possibility of fully practicing the ideas we believe in, learning from concrete experiences becomes crucial and we think that there is a lot to learn from the experiences of the Kurdish movement. More important than analyzing the perfect ideology, it is much needed to hear from people that have experienced with their own eyes a whole society (and not organisations of tens, or hundred people) trying to put self-management and autonomy into practice, taking themselves and their commitments seriously, believing that what they’re striving for could actually be achieved.

Also, it becomes more and more clear, the need for the radical left to approach problems with more pragmatism and less ideological purism. To get out of certain bubbles of self-assuredness, of believing to be free in the small islands that have been created over the years. To rethink what one perceives as radical and what not, to learn again how to engage with broader parts of society and to really start creating the alternative we want to live.

Links

- internationalistcommune.com

- makerojavagreenagain.org

- womendefendrojava.net

- riseup4rojava.org

- Internationalist Comune: materials

- Social Ecology

- Ecologie Sociale Liege

- demned.nl